In case you missed it, on June 15, (now former) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt signed a proposed action to establish no additional regulatory requirements under the Clean Water Act (CWA) section 311(j)(1)(C) authority for CWA hazardous substances (HS) discharge prevention. The EPA published the Notice of Propose Rulemaking (NPRM) on June 25, 2018 (83 FR 29499). This action was commonly referred to as a “Chemical Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) Plan”.

This is a mixed bag. There certainly is relief that industrial facilities with hazardous chemical storage tanks will not be required to develop these new plans (at least for the foreseeable future). It is also a relief that the EPA did not rush a rule to placate environmental groups. However, it still does boggle the mind the EPA does not require any proactive spill control plans for hazardous substances other than oil.

In July 2015, The Environmental Justice Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform (EJHA) and People Concerned About Chemical Safety (PCACS), joined by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), sued the EPA, citing its decades-long failure to prevent and contain the discharge of dangerous chemicals from thousands of industrial facilities around the country. The lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, asks the court to require EPA to issue regulations to prevent hazardous substance spills from non-transportation related industrial facilities, including above-ground storage tanks. Although Congress mandated that the EPA issue these regulations “as soon as possible” in 1972, the agency has never done so. On February 16, 2016, the U. S. District Court for the Southern District of New York entered a Consent Decree that required EPA to sign a notice of proposed rulemaking pertaining to the issuance of hazardous substance regulations. The Consent Decree also requires the EPA to take final action after notice and comment on said notice.

As a result of the Consent Decree, the EPA held three public meetings in 2016 to gain early input from stakeholders. The EPA also conducted information requests in 2017 to further develop the regulatory action.

In the preamble to the proposed no action, the EPA presented data based on an analysis of all calls of CWA HS discharges reported to the National Response Center (NRC) over a 10-year period to estimate the frequency of CWA HS discharges to better understand the impacts of these potential discharges to the communities affected. EPA determined that out of 285,867 releases reported to the NRC, less than 1% (2,491) involved substances included as CWA HS from non-transportation related facilities. Further dissection of the data indicated that 117 of these releases resulted in impacts to water supplies or resulted in waterway closures, evacuations, injuries, hospitalizations, and/or fatalities. Over 80% of these releases contained the following chemicals: Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), Sulfuric Acid (>80%), Sodium Hydroxide, Ammonia, Benzene, Hydrochloric Acid, Chlorine (liquid), Sodium Hypochlorite, Toluene, Phosphoric Acid, Styrene, Nitric Acid (fuming), and Potassium Hydroxide.

The EPA also looked at existing requirements under the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) including the OSHA General Duty Clause, Process Safety Management (PSM), Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER), Hazard Communication Standard and Emergency Action Plans(EAPs), the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), and other EPA regulations. Specifically, the EPA regulations reviewed included: NPDES Multi-Sector General Permit (MSGP) for Industrial Stormwater, Risk Management Plans under the Clean Air Act, Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) Plans, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) requirements for generators of hazardous waste and treatment storage and disposal facilities, and the RCRA requirements for underground storage tanks (USTs) and under the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA) for emergency planning, chemical release reporting, and chemical inventory storage reporting.

The analysis indicates that there are existing cumulative EPA regulatory requirements under various programs for accident and discharge prevention relevant to CWA HS. Similarly, existing cumulative requirements under Federal regulatory programs administered by other Federal agencies and departments (i.e., OSHA, MSHA, PHMSA, and OSMRE) reflect, under various accident and discharge prevention programs.

While this analysis indicated there are existing regulatory programs that reflect some aspects of an effective chemical spill prevention plan, there is no current or proposed rule that spells out specific requirements. This leaves industry to fill in the blanks and guess what the EPA would consider appropriate measures. Now this really won’t matter to most industries, UNTIL, they have a release.

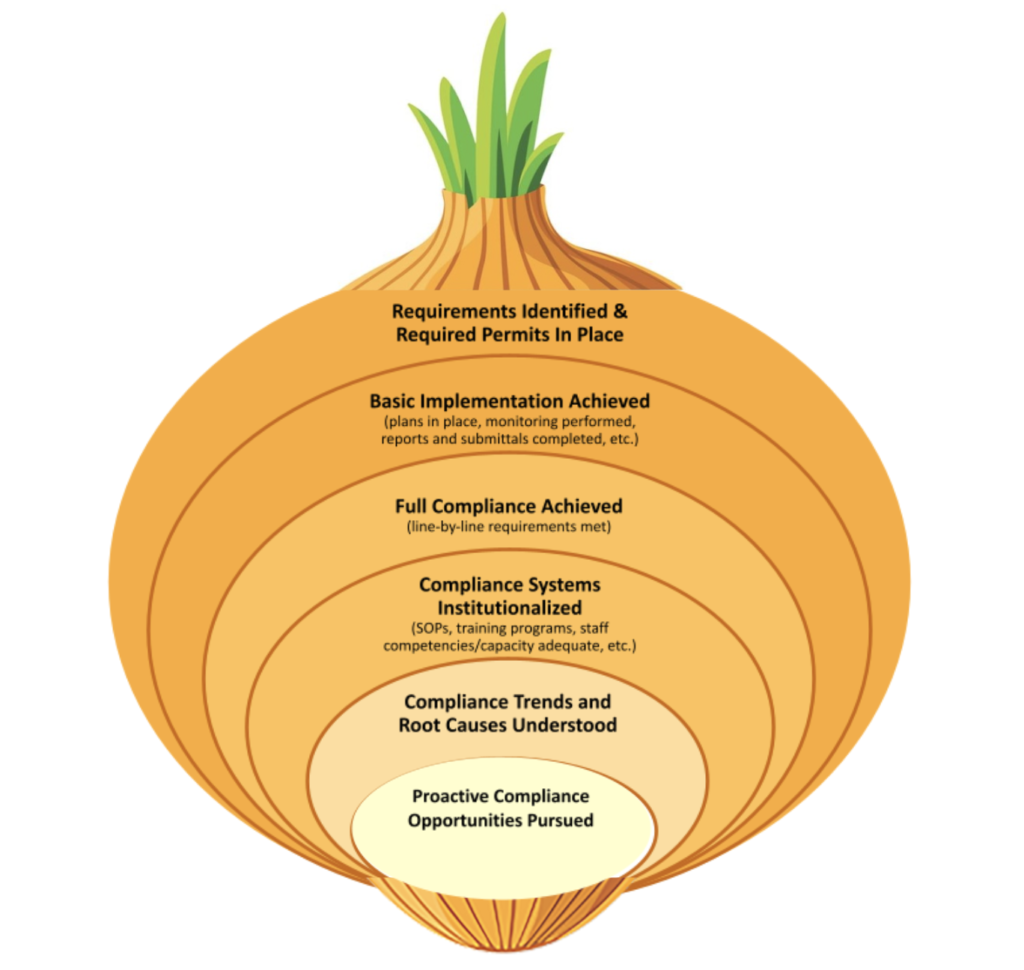

In light of the lack of any new regulations regarding chemical spill prevention, it’s important to focus on proactive planning and prevention measures, in particular the development of a proactive management program. By focusing on a proactive spill management approach, you can reduce costs and limit potential liability following environmental releases of hazardous materials, fuel and other regulated materials. The key to implementing an effective spill prevention plan is having an accurate chemical inventory with locations in excess of reportable quantities, a preventive maintenance and inspection program and a well-trained team.

Robert A. (Bob) LaRosa, P.E. is an experienced environmental professional with over 30 years’ experience in the EH&S field in various field level, supervisory, and management positions. He is a senior staff member with AARCHER and has worked with clients in the manufacturing, chemical, petroleum, transportation, telecommunication, food and pharmaceutical industries to improve their environmental, health and safety programs and performance. He is a registered professional engineer in several states and serves as both an AARCHER consultant and instructor for the Aarcher Institute of Environmental Training. He can be reached at [email protected].

Robert A. (Bob) LaRosa, P.E. is an experienced environmental professional with over 30 years’ experience in the EH&S field in various field level, supervisory, and management positions. He is a senior staff member with AARCHER and has worked with clients in the manufacturing, chemical, petroleum, transportation, telecommunication, food and pharmaceutical industries to improve their environmental, health and safety programs and performance. He is a registered professional engineer in several states and serves as both an AARCHER consultant and instructor for the Aarcher Institute of Environmental Training. He can be reached at [email protected].

When audits are initiated in response to an outside requirement to perform an audit, simply obtaining a competent audit at a competitive cost may be the perfect solution. In these cases, audit quality isn’t as much of a concern as clearing the pass-fail bar as efficiently as possible. Of course, the audit must be performed in a professional manner and the results need to be adequately documented in a report. The federal government would call this the “lowest cost, technically acceptable” standard. If this sounds like you, your path forward is fairly clear and you should probably skip over the rest of this post.

When audits are initiated in response to an outside requirement to perform an audit, simply obtaining a competent audit at a competitive cost may be the perfect solution. In these cases, audit quality isn’t as much of a concern as clearing the pass-fail bar as efficiently as possible. Of course, the audit must be performed in a professional manner and the results need to be adequately documented in a report. The federal government would call this the “lowest cost, technically acceptable” standard. If this sounds like you, your path forward is fairly clear and you should probably skip over the rest of this post.

March 1 is the deadline for submission of EPCRA Tier II forms.

March 1 is the deadline for submission of EPCRA Tier II forms. Bob LaRosa, PE, is a professional environmental engineer with more than 30 years of experience. He has assisted Federal and private clients with a variety of environmental support projects, including multimedia compliance auditing, EH&S training and curriculum development, SPCC plan development, hazardous materials and hazardous waste management plan development, water system management plan development and implementation, and ESAs.

Bob LaRosa, PE, is a professional environmental engineer with more than 30 years of experience. He has assisted Federal and private clients with a variety of environmental support projects, including multimedia compliance auditing, EH&S training and curriculum development, SPCC plan development, hazardous materials and hazardous waste management plan development, water system management plan development and implementation, and ESAs. The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) hazardous waste manifest system is designed to track hazardous waste from the time it leaves the generator facility where it was produced, until it reaches the off-site waste management facility that will store, treat or dispose of the hazardous waste. In 2014, the EPA established a national system for tracking hazardous waste shipments electronically. This system, known as “e-Manifest,” is intended to modernize the nation’s cradle-to-grave hazardous waste tracking process while saving valuable time, resources, and dollars for industry and states. EPA launched e-Manifest on June 30, 2018, along with user fees to offset the cost of the EPA developing the electronic manifest.

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) hazardous waste manifest system is designed to track hazardous waste from the time it leaves the generator facility where it was produced, until it reaches the off-site waste management facility that will store, treat or dispose of the hazardous waste. In 2014, the EPA established a national system for tracking hazardous waste shipments electronically. This system, known as “e-Manifest,” is intended to modernize the nation’s cradle-to-grave hazardous waste tracking process while saving valuable time, resources, and dollars for industry and states. EPA launched e-Manifest on June 30, 2018, along with user fees to offset the cost of the EPA developing the electronic manifest. Robert A. (Bob) LaRosa, P.E. is an experienced environmental professional with over 30 years’ experience in the EH&S field in various field level, supervisory, and management positions. As a consulting engineer he has worked with clients in the manufacturing, chemical, petroleum, transportation, telecommunication, food and pharmaceutical industries to improve their environmental, health and safety programs and performance. He is a registered professional engineer in several states and serves as both an AARCHER consultant and instructor for the Aarcher Institute of Environmental Training. He can be reached at

Robert A. (Bob) LaRosa, P.E. is an experienced environmental professional with over 30 years’ experience in the EH&S field in various field level, supervisory, and management positions. As a consulting engineer he has worked with clients in the manufacturing, chemical, petroleum, transportation, telecommunication, food and pharmaceutical industries to improve their environmental, health and safety programs and performance. He is a registered professional engineer in several states and serves as both an AARCHER consultant and instructor for the Aarcher Institute of Environmental Training. He can be reached at

I had the opportunity, over four days, to walk through the neighborhoods of Paris and see the different expressions of architecture in this city. From the stately manors along Chickasaw Road, the commercial center along E Wood Street, and to the quiet streets near the Henry County Fairgrounds. The buildings expressed the economic hope and optimism of the 1950’s and 1960’s. The northern end of my radius included farmland where curious dogs and horses wondered who this stranger was and why was he taking pictures.

I had the opportunity, over four days, to walk through the neighborhoods of Paris and see the different expressions of architecture in this city. From the stately manors along Chickasaw Road, the commercial center along E Wood Street, and to the quiet streets near the Henry County Fairgrounds. The buildings expressed the economic hope and optimism of the 1950’s and 1960’s. The northern end of my radius included farmland where curious dogs and horses wondered who this stranger was and why was he taking pictures. hile documenting the structures in Paris we are also collecting data to access these properties. The assessment is done to determine if they may be eligible for listing upon the National Register for Historic Places (NRHP). With a combination architectural styles popular in the post-WWII era (contemporary, minimal traditional, ranch, shed, and split-level) the neighborhoods of the eastern side of Paris are a reflection of that time. After this data was collected it was given to the Tennessee Historical Commission so that it may provide a tool in the future with regards to planning decisions. The architectural survey is a means to evaluate the impact that a proposed development project would have upon historic resources also provided a means to better understand these resources in the future. It is this way that the work that Aarcher performs is a benefit to our clients and to the communities we work in.

hile documenting the structures in Paris we are also collecting data to access these properties. The assessment is done to determine if they may be eligible for listing upon the National Register for Historic Places (NRHP). With a combination architectural styles popular in the post-WWII era (contemporary, minimal traditional, ranch, shed, and split-level) the neighborhoods of the eastern side of Paris are a reflection of that time. After this data was collected it was given to the Tennessee Historical Commission so that it may provide a tool in the future with regards to planning decisions. The architectural survey is a means to evaluate the impact that a proposed development project would have upon historic resources also provided a means to better understand these resources in the future. It is this way that the work that Aarcher performs is a benefit to our clients and to the communities we work in.

Back to the eerie mountain top. I find myself there to access the direct effects that constructing a tower compound will have on potential historic resources. They are potential because this area had not been previously tested by professional archaeologists. So there was the chance that there could be something here. I am there with my trusty tools: shovel, screen, and trowel. Before digging can commence, a walk-over of the project area is conducted to locate historic resources on the surface. And that is when I saw it.

Back to the eerie mountain top. I find myself there to access the direct effects that constructing a tower compound will have on potential historic resources. They are potential because this area had not been previously tested by professional archaeologists. So there was the chance that there could be something here. I am there with my trusty tools: shovel, screen, and trowel. Before digging can commence, a walk-over of the project area is conducted to locate historic resources on the surface. And that is when I saw it. First I would need to change my tool. I found a fallen stick about my height and used my machete to trim the twigs off of it, creating a probe and walking stick. I had three things to worry about: wet leaves, wet moss, and wet rocks. Second, I walked around the perimeter of the project area placing flags so that I could turn the project area into a grid. Third, I slowly walked the X- and Y-axis of the grid to look for signs of human activity.

First I would need to change my tool. I found a fallen stick about my height and used my machete to trim the twigs off of it, creating a probe and walking stick. I had three things to worry about: wet leaves, wet moss, and wet rocks. Second, I walked around the perimeter of the project area placing flags so that I could turn the project area into a grid. Third, I slowly walked the X- and Y-axis of the grid to look for signs of human activity.